You’ve heard it repeated so many times, by both industry advocates and adversaries: “There’s not enough research. We need more research! We don’t know enough about the medical benefits of cannabis.” The problem with this statement is that, while it contains some truth, it is ultimately false. The truth? There is absolutely a need for more cannabis research. But when this argument is used to maintain the current prohibitions until more research is done, it is dangerously short-sighted. To be clear: there has already been more than enough research to tell us that cannabis use is safer than cannabis prohibition. We also have pre-clinical and mounting anecdotal evidence suggesting a long list of potential benefits that could save (or improve) countless lives. Controlled clinical trials on humans are happening now around the world, and we can all agree that we need more to better understand this plant’s medicinal capabilities.

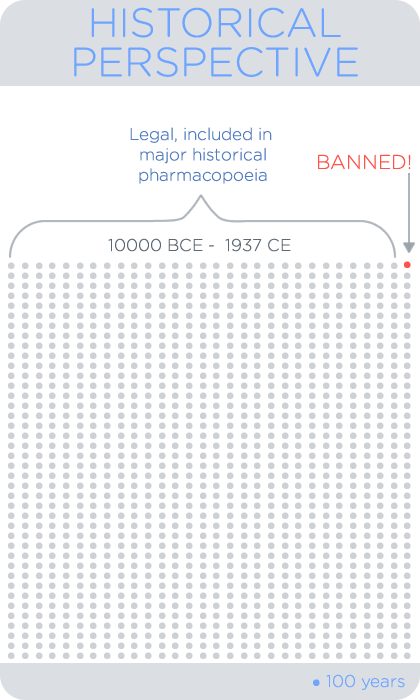

Research has also shown that it does not cause violent behavior or act as a gateway to harder drugs. A prohibitionist view based on a perceived lack of research overlooks the fact that humans have cultivated cannabis for at least the past 12,000 years, and ignores the many extensive studies done during the past 200 or so. Worse, it implies that we are somehow safer or better off by continuing to prevent patients from having safe access and arresting three quarters of a million people* every year until we reach the unspecified threshold of “enough” research.

Research has also shown that it does not cause violent behavior or act as a gateway to harder drugs. A prohibitionist view based on a perceived lack of research overlooks the fact that humans have cultivated cannabis for at least the past 12,000 years, and ignores the many extensive studies done during the past 200 or so. Worse, it implies that we are somehow safer or better off by continuing to prevent patients from having safe access and arresting three quarters of a million people* every year until we reach the unspecified threshold of “enough” research.

Opponents have repeatedly tried to make a connection between cannabis and mental illness, but if there was a direct causal link between cannabis use and psychosis, it follows that the number of diagnoses of psychosis would rise with the increasing prevalence of cannabis use in society. It has not. According to government surveys, some 25 million Americans have smoked marijuana in the past year, and more than 14 million do so regularly. We know that, in California, one in 20 adults (or about 1.4 million people) have used medical cannabis to help treat an illness or condition. Of those Californians, a whopping 92% felt medical cannabis was helpful in treating their disease or illness. We know that deaths from prescription opiates have fallen 25% in states where medical cannabis is legal. Certainly there is still much we do not know, but what we do know tells us, in the words of the DEA’s administrative law judge Francis Young, that it is “unreasonable, arbitrary and capricious for DEA to continue to stand between […] sufferers and the benefits of this substance.”

And we know that, in order to achieve the current legal and regulatory status of cannabis, it has been necessary to ignore a massive amount of research:

1894: The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report

This 3,281-page, seven-volume classic report on the marijuana problem in India by the British concluded: “Viewing the subject generally, it may be added that moderate use of these drugs is the rule, and that the excessive use is comparatively exceptional. The moderate use produces practically no ill effects.” Nothing of significance in the report’s conclusions has been proven wrong in the intervening century.

1916 – 1929: Panama Canal Zone Military Investigations into Marijuana

After an exhaustive study of the smoking of marijuana among American soldiers stationed in the zone, the panel of civilian and military experts recommended that “no steps be taken by the Canal Zone authorities to prevent the sale or use of Marihuana.” The committee also concluded that “there is no evidence that Marihuana as grown and used [in the Canal Zone] is a ‘habit-forming’ drug.”

1944: The LaGuardia Report

This study is viewed by many experts as the best study of any drug viewed in its social, medical, and legal context. The committee covered thousands of years of the history of marijuana and also made a detailed examination of conditions In New York City. Among its conclusions: “The practice of smoking marihuana does not lead to addiction in the medical sense of the word.” And: “The use of marihuana does not lead to morphine or heroin or cocaine addiction, and no effort is made to create a market for those narcotics by stimulating the practice of marihuana smoking.”

The study also noted that “The majority of marihuana smokers are Negroes and Latin-Americans” and that “The consensus among marihuana smokers is that the use of the drug creates a definite feeling of adequacy.”

1968: The Wootton Report

This study report on marijuana and hashish was prepared by a group that included some of the leading drug abuse experts of the United Kingdom. These impartial experts worked as a subcommittee under the lead of Baroness Wootton of Abinger. The basic tone and substantive conclusions were similar to all of the other great commission reports. The Wootton group specifically endorsed the conclusions of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission and the La Guardia Committee. Typical findings included the following:

- There is no evidence that in Western society serious physical dangers are directly associated with the smoking of cannabis.

- It can clearly be argued on the world picture that cannabis use does not lead to heroin addiction.

- The evidence of a link with violent crime is far stronger with alcohol than with the smoking of cannabis.

- There is no evidence that this activity … is producing in otherwise normal people conditions of dependence or psychosis, requiring medical treatment.

1972: The Report of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, entitled “Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding”

This commission was directed by Raymond P. Shafer, former Republican governor of Pennsylvania, and had four sitting, elected politicians among its eleven members. The commission also had leading addiction scholars among its members and staff and was appointed by President Nixon in the midst of the drug-war hysteria at that time. The first recommendations of the commission were:

- Possession of marihuana for personal use would no longer be an offense.

- Casual distribution of small amounts of marihuana for no remuneration, or insignificant remuneration not involving profit, would no longer be an offense.

The recommendations in this reports were endorsed by (among others) the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, The American Association for Public Health, the National Education Association, and the National Council of Churches.

1980: The Facts About Drug Abuse, from the Drug Abuse Council

A 1972 report to the Ford Foundation, “Dealing With Drug Abuse,” concluded that current drug policies were unlikely to eliminate or greatly affect drug abuse. This conclusion led to the creation and joint funding by four major foundations of a broadly based, independent national Drug Abuse Council. The Council concluded, in part:

- Psychoactive substances have been available throughout recorded history and will remain so. To try to eliminate them completely is unrealistic.

- The use of psychoactive drugs is pervasive, but misuse is much less frequent, and the failure to make the distinction between use and misuse creates the impression that all use is misuse and leads to addiction.

- There is a clear relationship between drug misuse and pervasive societal ills such as poverty, racial discrimination, and unemployment, and we can expect drug misuse so long as these adverse social conditions exist.

1988: DEA Docket No. 86-22, MARIJUANA RESCHEDULING PETITION

Before issuing his ruling, The DEA’s own Chief Administrative Law Judge Francis Young heard two years of testimony from both sides of the issue and accumulated fifteen volumes of research. This was undoubtedly the most comprehensive study of medical marijuana done to date. Judge Young concluded that marijuana was one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man, that it had never caused a single human death, and that the Federal Government’s policy toward medical marijuana is “unconscionable.”

How much is enough?

It’s a little overwhelming, looking at all the evidence that’s been presented over the years, and then considering how different the world might be if we had followed the research that’s already been done. If the 1972 recommendation that “possession of marijuana should no longer be an offense” had been followed, there would have been somewhere in the neighborhood of 12,000,000 fewer arrests made between then and now. Individuals whose lives will never be the same. Families, whole communities left devastated. Meanwhile, the FDA recently approved OxyContin for children as young as 11, while we are in the midst of a prescription painkiller overdose epidemic.

Wouldn’t the money spent to enforce this failed prohibition on cannabis be better spent doing more research? How many lives could we save? How many jobs could we create?

*US average annual marijuana arrests, 1996 – 2012: 763,348